For more than five centuries the Doctrine of Discovery and the international law based upon it have legalized the theft of land, labor, and resources from Indigenous peoples across the world and systematically denied their human rights.

The Doctrine of Discovery originated with the Christian church and was based on Christian scripture, including the Great Commission, the divine mandate to rule based on Romans 13, and the narrative of a covenantal people justified in taking possession of land as described in the Exodus story.

Today Indigenous people in our country are among the most vulnerable on the planet due to this systemic injustice. But outside of Indigenous people and scholars, few people are aware of the Doctrine and its lasting impacts.

Contrary to what so many Americans learn in school, Columbus did not land in a sparsely settled, nearly pristine wilderness.

9500-7500 BCE Paleo-Indians traveled in what is known now as Iowa, hunting and gathering. As the climate changed, the region became more conducive to living.

7500-5500 BCE Small numbers of people lived in the region at least on a seasonal basis.

2500-500 BCE Evidence of burial sites and more permanent settlements.

1000-1650 CE Native peoples adjust to prairie life, planting and gathering, building earth lodge houses and hunting.

Europeans begin exploring the waters and inlets of the North American continent as early as the 12th century. As they come into contact with Indigenous populations, they also introduce diseases where there was no immunity. Indigenous populations begin to drop precipitously, and the extermination of tens of millions of people helps create the illusion that the newly available lands were nearly empty of human inhabitants.

Drawing accompanying text in Book XII of the 16th-century Florentine Codex (compiled 1540–1585), showing Nahuas of conquest-era central Mexico suffering from smallpox, picture Wikimedia

Christopher Columbus’ “discovery” of the Americas in 1492 feeds a frenzy of 16th century exploration, exploitation, and conquest based on the proclamation by Pope Nicholas V giving rights and control of ownership to those who got there first. This same pronouncement sanctions the enslavement of African people by Europeans. The first enslaved Africans arrive in Hispaniola in 1501 soon after the Papal Bull of 1493 gives all of the “New World” to Spain. The use of slave labor is deemed necessary, in part, due to the extermination of local Indigenous populations from violence and disease.

The first Africans to reach the English colonies arrive in Virginia in 1619, brought by Dutch traders who had seized them from a captured Spanish slave ship. The Spanish usually baptized slaves in Africa before embarking them. Since English law considers baptized Christians exempt from slavery, these Africans are treated as indentured servants, joining about 1,000 English indentured servants already in the colony.

The transformation of the status of Africans from indentured servitude, which was temporary, to slavery, which they could not leave or escape, happens gradually. By 1705, the Virginia slave codes define as slaves those people who are imported from nations that were not Christian—an idea drawn from the Doctrine of Discovery. Indigenous people sold to colonists by other tribes or captured by Europeans during village raids are also defined as slaves. This code serves as a model for the other colonies.

From the 1705 Virginia Slave Codes:

“All servants imported and brought into the Country...who were not Christians in their native Country...shall be accounted and be slaves. All Negro, mulatto and Indian slaves within this dominion... shall be held to be real estate. If any slave resist his master... correcting such slave, and shall happen to be killed in such correction...the master shall be free of all punishment...as if such accident never happened.”

Massachusetts Bay Colonies

Indigenous tribes, some of whom suffer from the onslaught of European diseases, also develop a hostile, violent, and deeply distrustful relationship with the Puritans. The Puritans abduct some of the Indigenous people to ship to England. In 1633, a law is passed to require that Indigenous people would only receive “allotments” and “plantations” if they “civilized” themselves by becoming Puritans and accepting English customs of agriculture and living. —www.quaqua.org/pilgrimage

Iowa

In the summer of 1673, Louis Joliet and Father Jaques Marquette travel down the Mississippi River past the land that was to be called Iowa. This may well have been the first Europeans to visit the region. Before 1673, the region had been home to many people in about 17 different tribes including the Ioway, Sauk, Meskwaki, Sioux, Potawatomi, Oto, and Missouri. —“History of Iowa” by Dorothy Schwieder, professor of history at Iowa State University

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680

After the Spanish establish a colony in New Mexico’s Rio Grande Valley in 1598, they seize Indigenous land and crops and force the people to labor in settlement fields and in weaving shops. The Indigenous people are denied religious freedom, and some are executed for practicing their spiritual religion.

The pueblos are independent villages with several distinct languages. Occasionally an uprising against the Spanish begins in one pueblo, but it is squashed before it can spread to neighboring pueblos. Leaders are hanged, others enslaved.

In 1675, the Spanish arrest forty-seven medicine men from the pueblo, and try them for witchcraft. Four are publicly hanged; the other forty-three are whipped and imprisoned. Among them is Popé, a medicine man from San Juan. The forty-three are eventually released, but the damage has been done and the anger runs deep. Popé recruits leaders in other pueblos to plan the overthrow of the Spanish.

In August of 1680, the Pueblo people attack northern settlements. Spanish settlers flee to the governor’s enclosure at Santa Fe. They are surrounded, and after a few days’ siege, the settlers retreat to the south.

Although the Indigenous people kill 400 Spaniards and succeed in driving out the rest of the colonists, they do not continue their confederation. As a consequence, the Spanish are eventually able to re-establish their authority. By 1692, they reoccupy Santa Fe, but they do not return to their authoritarian ways. The continuation of Indigenous traditions is somewhat tolerated. Pueblo people are able to maintain a great deal of their traditional ways because of the respect they won in the 1680 rebellion. —Adapted from Encyclopedia.com

The Lenape and Penn’s “Holy Experiment”

Invited by William Penn and fleeing persecution in Europe, Amish and Mennonites begin arriving in Pennsylvania. Penn had been granted the historic lands of the Lenape people by the King of England, which had laid claim to the land under the Doctrine of Discovery. Once Penn receives the charter to the lands, he realizes that much of it is held by Indigenous people, who would expect payment in exchange for vacating the territory.

In 1737, after Penn’s death, his sons cheat the Lenape out of their lands in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania through the infamous Walking Purchase. Because of the Walking Purchase, the Lenape grow to distrust the Pennsylvania government, and its once good relationship with the various tribes is lost.

Attack on the Conestoga

In the aftermath of the French and Indian War, the frontier of Pennsylvania remained unsettled. A new wave of Scots-Irish immigrants encroaches on Indigenous people’s lands in the backcountry. These settlers claim that Indigenous people often raid their homes, killing men, women, and children. Reverend John Elder, who is the parson at Paxtang and Derry (near Harrisburg), becomes the leader of the settlers. Elder helps organize the settlers into a motivated militia known as the “Paxton Boys.”

Although there have been no attacks in the area, the Paxton Boys claim that the Conestoga secretly provide aid and intelligence to the hostiles. On December 14, 1763 more than fifty Paxton Boys march on Conestoga homes near Conestoga town (now Millersville), murder six, and burn their cabins. The colonial government holds an inquest and determines that the killings were murder. Governor John Penn offers a reward for the capture of the Paxton Boys.

1841 lithograph of the Paxton Boys' massacre of the Indians at Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1763, picture Wikimedia

The remaining sixteen Conestoga are placed in protective custody in Lancaster but the Paxton Boys break in on December 27, 1763. They kill and scalp six adults and eight children. The attackers are never identified.

“The doctrine [of Discovery], known in church laws as Inter Cetera, forms the basis of Indian law in what was to become the United States, justifying in the minds and courts of white settlers that they could divide up land ownership without regard for the millions of natives who had lived here for millennia. The protections intended in the separation of church and state were conveniently not extended to the Indians.

When the leaders of the American Revolution pledged their honor and fortunes in the fight to break free from England, those fortunes in many cases were based on huge profits pocketed by land speculators like Washington, Jefferson, and Adams, who relied on the doctrine to survey, subdivide and claim ownership of lands with no consideration for the indigenous people living on them.”

— Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Turtle Clan and a member of the Onondaga National Council of Chiefs of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) confederacy, written in Albany Times Union on Sunday, August 9, 2009

The Proclamation of 1763

… issued by King George, tells the colonies that they no longer have the “right of discovery” to Indigenous lands west of Appalachia. Only the British Crown could thereafter negotiate treaties and buy or sell those lands. This Proclamation deeply upset the colonies, who want access to those lands. In the Declaration of Independence, this royal proclamation is cited in the long list of justifications for why the colonies declare independence from British control. Following the defeat of the British during the Revolutionary War, the Treaty of Paris (1783) gives these Indigenous lands to the new U.S. government.

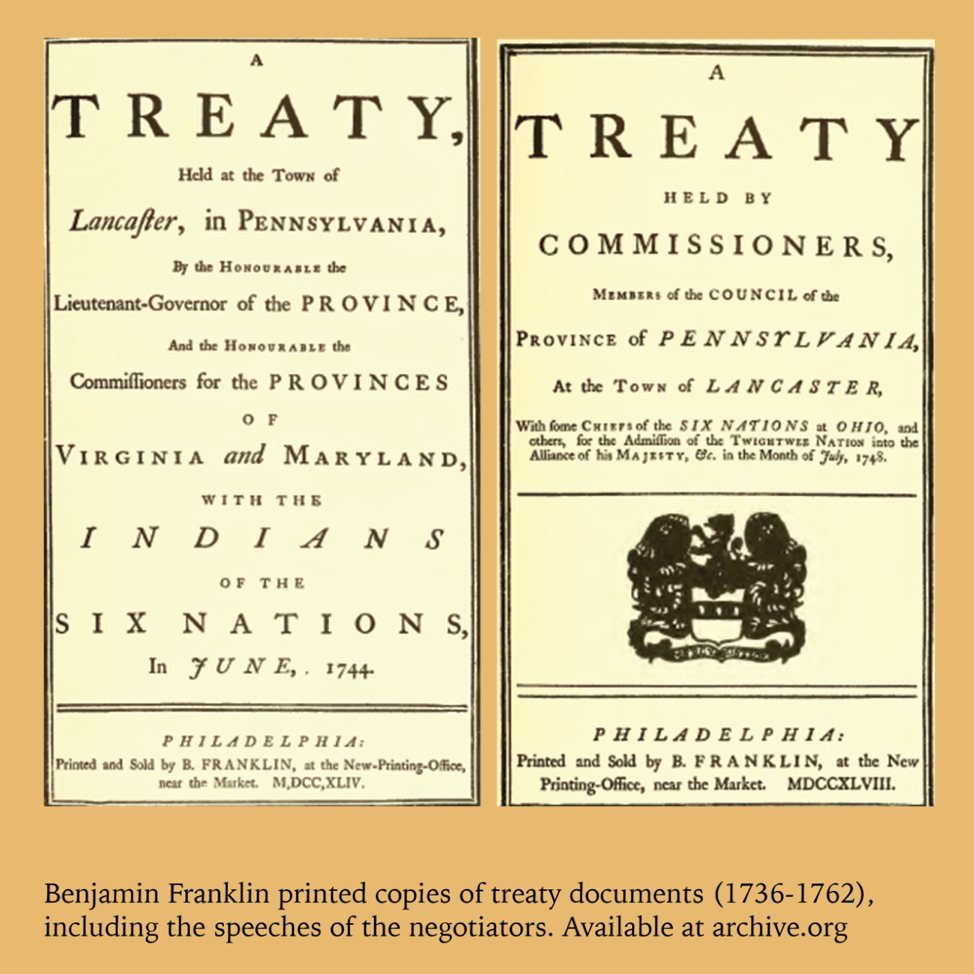

Broken Treaties

From the time of the American Revolution, the U.S. made treaties with Indigenous nations as sovereign nation to sovereign nation. While Indigenous nations understand treaties to be sacred agreements witnessed by the Creator, the U.S. repeatedly breaks and violates treaties as their desire to acquire more land increases. In all, over 500 treaties are changed, nullified or broken. The result is an ever-increasing land base for the U.S. as tribes are pushed farther and farther west. Each time a treaty is broken, land is taken and tribes are forced out, while white Europeans follow shortly to settle the land.

Removal Era 1830-1850

The Indian Removal Act is passed by Congress in 1830, during the presidency of Andrew Jackson. This Act gives power to the government to make treaties with Native nations that force them to give up their lands in exchange for land west of the Mississippi. These treaties, on the surface, speak to a voluntary exchange and removal of nations. However, in reality, most of these treaties are made forcefully, by withholding food — through the decimation of food sources, such as the buffalo — and through violence, including warfare. As Native American lands are “cleared,” white settlers stream into those lands.

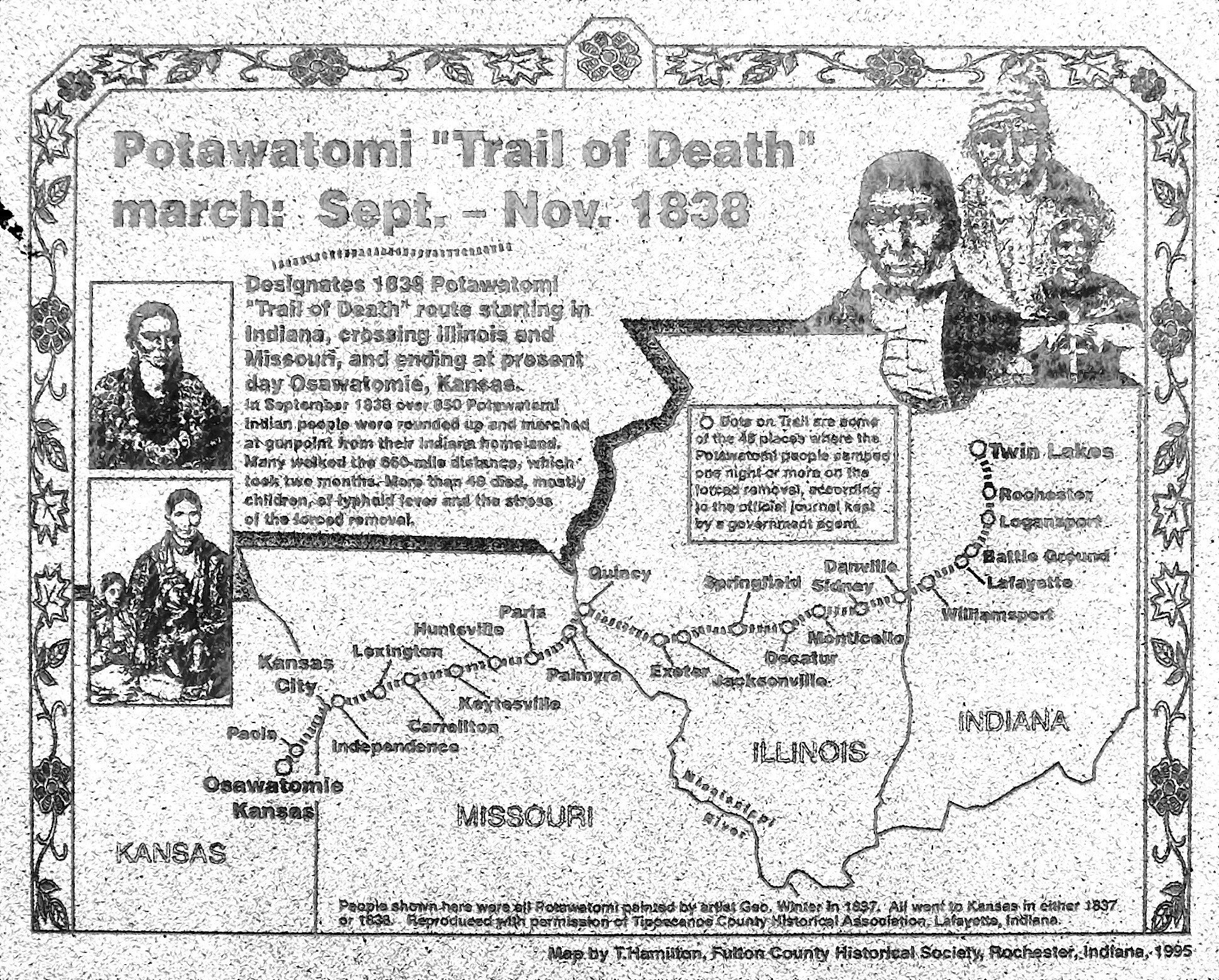

Trail of Death

Not as well known as the Cherokee Trail of Tears is the Trail of Death, which completes the removal of around 800 Potowatomi people from northern Indiana and southern Michigan to present-day eastern Kansas in 1838. They forcibly marched about 660 miles and escorted by armed militia from Indiana, through Illinois and Missouri, into present-day Osawatomie, Kansas. During the march 42 people die, 28 of them children.

Reservation Era 1850-1887

U.S. victory in the Mexican American War and the California Gold Rush puts pressure on the U.S. government to further restrict the territories of Indigenous tribes so that white settlers can move onto their lands. The U.S. government begins to confine Indigenous people to reservations. Indigenous people resist the reservation system and engage with the U.S. Army in what are called the “Indian Wars” in the West for decades. Finally defeated by the military and continuing waves of encroaching settlers, the tribes negotiate agreements to resettle on reservations.

Chief Black Hawk

In 1832, Chief Black Hawk, Sauk leader, protested the movement of the Sauk from their land in Western Illinois. As punishment for the resistance, the Sauk and Meskwaki are forced to relinquish some of their land in western Illinois and eastern Iowa. It is after June 1, 1833, under the terms of the Treaty known as the Black Hawk Purchase, that European settlement in the Iowa Territory begins in earnest and the Sauk and Meskwaki are moved to a reservation in Kansas.

By 1851, all Indigenous lands in Iowa are claimed by the U.S. government and the General Land Office surveys quickly divide up the lands for sale. In 1856, the Meskwaki Chief, Mamenwaneke, succeeds in petitioning Governor James Grimes to allow the tribe to purchase 80 acres of land in Tama County, Iowa.

Dakota War of 1862

In 1862, an armed conflict begins in Minnesota between the U.S. and several bands of Dakota after over a decade of treaty violations by the U.S. and late or unfair annuity payments causing increasing hunger and hardship among the Dakota.

By late December 1862, U.S. soldiers have taken captive more than a thousand Dakota, including women, children and elderly men in addition to warriors, who are interned in jails in Minnesota. After trials and sentencing by a military court, 38 Dakota men are hanged on December 26, 1962 in Mankato, Minnesota, in the largest one-day mass execution in American history. A total of 303 were sentenced to be hanged but President Lincoln pardons 265 after the persistent urging of the Rt. Rev. Henry Whipple (Episcopal Bishop of Minnesota) for Lincoln to re-examine the sentences. In April 1863, the rest of the Dakota are expelled from Minnesota and moved to Camp McClellan in Davenport, Iowa where they are imprisoned for almost four years. By the time of their release, one-third of the prisoners had died of disease. The survivors are sent to Nebraska to join their other family members who had been expelled from Minnesota.

The Doctrine of Discovery in the U.S. Law

Chief Justice John Marshall

Johnson v. McIntosh

In 1873, the Christian Doctrine of Discovery is quietly adopted into U.S. law by the Supreme Court in Johnson v. McIntosh. Waiting for a unanimous court, Chief Justice John Marshall observes that Christian European nations have assumed “ultimate dominion” over the lands of America during the Age of Discovery, and that — upon “discovery” — the Indigenous people had lost “their rights to complete sovereignty as independent nations, and only retained a right of “occupancy” in their lands. In other words, Indigenous nations were subject to the ultimate authority of the first nation of Christendom to claim possession of indigenous people’s lands.

According to Marshall, the United States — upon winning its independence in 1776 — became a successor nation to the right of “discovery” and acquired the power of “dominion” from Great Britain.

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

In 1828, the state of Georgia passes a series of laws stripping local Cherokees of their rights and also authorizing Cherokee removal from their lands. In defense, the Cherokee cite treaties that they had negotiated with the U.S., guaranteeing them both the land and their independence. After failed negotiations with President Andrew Jackson and Congress, the Cherokees seek an injunction against Georgia to prevent its carrying out these laws. The Supreme Court rules that it lacks jurisdiction to hear the case and cannot resolve it, since the Cherokee, through sometimes viewed as an independent nation, are also dependent people on the U.S. nation that envelops them. Because the Constitution only authorizes the Supreme Court to hear cases brought by “foreign nations,” not “Indian nations,” the Supreme Court rules it is not authorized to entertain this case and dismisses it. (http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/landmark_cherokee.html)

Assimilation Era 1887-1934

A 1911 ad offering "allotted Indian land" for sale, picture Wikimedia

By the late 1870’s, the U.S. government begins to shift its policy toward Indigenous peoples to one of assimilation. Many consider the Indigenous way of life and collective use of the land to be communistic and backwards. They also regard the individual ownership of private property as an essential part of civilization that will give Indigenous people a reason to stay in one place, cultivate land, disregard the cohesiveness of the tribe, and adopt the habits, practices, and interests of the American settler population. Furthermore, many believe that Indigenous people have too much land and are eager to see their lands opened up for settlement as well as for railroads, mining, forestry and other industries.

Under the 1887 Allotment Act (Dawes Act), every Indigenous man 18 years or older is allotted 160 acres of land. After all Indigenous men are designated land, the rest is opened up for white settlement. Land the U.S. government allows Indigenous people to occupy is reduced by approximately by 2/3 by 1934. Of the land that remains unsettled, about 1/3 is unfit for most profitable uses, being desert or semi-desert land.

Boarding School History

Carlisle Indian Industrial School, picture Wikimedia

Another strategy for assimilating Indigenous peoples into white European culture is through education in boarding schools.

In 1879, Captain Richard Henry Pratt founds the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania by removing 84 Lakota children from their families in the Dakotas. His principle, “kill the Indian and save the man” becomes a model for new government policy. By 1900, thousands of children are attending close to 150 boarding schools throughout the U.S. The schools seek to completely strip children of their culture and remove them from the influence of their family and nation. Children are punished for dressing, acting, or speaking in ways that represent traditional practices.

Through the 19th and 20th centuries, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children are placed in over 350 boarding schools operated by the federal government and the churches. The Episcopal Church operated nine boarding schools, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

Boarding Schools in Iowa

In 1881, Benjamin and Elizabeth B. Miles begin a “Training School for Indian Children” in West Branch, Iowa. The government pays them $167 per year per Indigenous student and soon they are filled to capacity. They decide to lease the former White’s Iowa Manual Labor Institute in Lee County that had been previously filled with juvenile wards of the state and relocate there in 1883. By 1886 they report that seventy-five Indians and thirteen white children are enrolled and that forty-eight of them have been received into the membership of the Society of Friends. In 1887, the building is destroyed by fire.

In 1898, the U.S. government opens a boarding school in Toledo, Iowa without the support of Meskwaki leaders. Although some students went home on weekends, the boarding school disrupted tribal life and took children away from their parents. The government could not legally force Meskwaki children to attend the school, but some government officials tried. Parents went to court to stop them. Because so few Meskwaki children attended the boarding school, Indigenous children were brought in from across the county. The school closed in 1910. — from iagenweb.org and iptv.org

The Rev. Vine Deloria

“In 1951, the first Episcopal priest in the Diocese of Iowa of Native American Indian heritage was named priest-in-charge of Trinity in Denison, Trinity Memorial in Mapleton, and St. John’s in Vail. The Reverend Vine Victor Deloria, canonically resident in the Diocese from October 1, 1951, was elected to the Standing Committee in 1953 and was awarded a fellowship to the College of Preachers in Washington, D.C. In 1954, he was appointed to be the Assistant to the Secretary of the Home Department of the National Council and after five years he returned to Iowa to become Vicar of St. Paul’s, Durant. He left the Diocese of Iowa in 1960.” — Loren Horton, The Beautiful Heritage: History of the Diocese of Iowa 1853-2003

St. Paul’s Indian Mission

St. Paul’s Indian Mission in Sioux City, Iowa

Episcopal work with Indigenous people in Sioux City, Iowa began in the 1950’s when a city-wide religious census noted 60 Episcopal Indian families who were not attending any of the three existing Episcopal churches in Sioux City. In 1961, a house is purchased for use as a spiritual, social, and educational center. In 1963, the Indian Council of Sioux City was organized and in 1964 the congregations of St. Paul’s and Calvary churches merged into one church. Members began to worship at Calvary and St. Paul’s was devoted exclusively to work with Native American Indians.

In 1969, some of the financial support for St. Paul’s Indian Mission comes from the Diocese of Iowa and by 1972 the Diocesan budget includes $12,000 for that purpose. In 1968 and 1970, St. Paul’s also receives grants from The Episcopal Church to support education and programs at the church. By 1972, St. Paul’s is serving an estimated 1,200 people, 200 of whom they report as being Episcopalians. — Loren Horton, The Beautiful Heritage: History of the Diocese of Iowa 1853-2003

Termination Era 1945-1961

In 1953, Congress adopts an official policy of “termination,” declaring that the goal is to “as rapidly as possible to make Indians within the territorial limits of the U.S. subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the U.S.” In addition to ending the tribal rights as sovereign nations, the policy terminates federal support of the health care and education programs and police and fire fighting departments available on reservations.

From 1953-1964, 109 tribes are terminated, and federal responsibility and jurisdiction is turned over to state governments. Approximately 2.5 million acres of trust land is removed from protected status. The lands are sold to non-indigenous people, and the tribes lose official recognition by the U.S. government. By 2018, many tribes, though not all, have regained federal recognition through long court battles, which for some tribes take decades and exhaust large sums of money.

2007 U.N. Declaration

After a generations-long effort by Indigenous organizations, the United Nations adopts a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Initially the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand vote against it (143 member states vote for; 11 abstain). It isn’t until three years later, under pressure from Indigenous Peoples and the international community, that the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand sign on.

Repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery

The Episcopal Church

In 2009, the 76th General Convention of The Episcopal Church repudiates and renounces the Doctrine of Discovery as “fundamentally opposed to the gospel of Jesus Christ and our understanding of the inherent rights that individuals and peoples have received from God.” The resolution calls for the church to examine and eliminate its policies, programs and structures that contribute to the continuing colonization of Indigenous peoples and directs the Office of Government Relations to advocate for the U.S. to sign the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Continued Threats

On December 12, 2014, Terry Rambles, the chairman of the San Carlos Apache Tribe woke up in Washington, D.C. to learn that Congress was deciding to give away a large part of his ancestral home land to a foreign mining company Rambler came to the nation’s capital for the White House Tribal Nations Conference, an event described in a press announcement as an opportunity to engage the president, cabinet officials, and the White House Council on Native American Affairs “on key issues facing tribes including respecting tribal sovereignty and upholding treaty and trust responsibilities,” among other things.

Rambler felt things got off to an unfortunate, if familiar, start when he learned that the House and Senate Armed Services Committee had decided to use the lame-duck session of Congress and the National Defense Authorization Act to give 2,400 acres of the Tonto National Forest in Arizona to a subsidiary of the Australian-English mining giant Rio Tinto.

Native Nations Rise March in Washington, D.C. on March 10, 2017. Photo by slowking

In 2016, another threat to Indigenous people emerges, as approval is given to the Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access Pipeline to run from western North Dakota to southern Illinois, crossing under the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers and under part of Lake Oahe near the Standing Rock Reservation. Many in the Standing Rock tribe consider the pipeline a threat to the region's water and to ancient burial grounds. Standing Rock Sioux elder LaDonna Brave Bull Allard establishes the Sacred Stone Camp as a center for cultural preservation and spiritual resistance to the pipeline which grows to thousands of people and draws considerable national and international attention and protests in solidarity. In Iowa, community and environmental activists and the Meskwaki Nation also stand in opposition to the pipeline, protesting the risk to Iowa’s aquifers.

On January 24, 2017, newly-elected President Donald Trump signs an executive order allowing the pipeline’s construction to proceed and on February 22, 2017, the camp is cleared after months of protests, legal battles, violent conflicts with private security and police, and many high-profile arrests. In June 2017, crude oil begins to flow through the Dakota Access Pipeline, transporting up to 520,000 barrels of oil daily.

Call to Action

The Doctrine of Discovery remains an international legal framework with Christian theological roots that still legitimizes the unjust exploitation of millions of Indigenous peoples at home and around the world. Their lands and waters, their very sources of life, are being poisoned and polluted. The resources extracted from these communities flow back to the colonizing powers through corporate profit and benefit mutual funds and investments.

Because the Doctrine is based on principles that originated with the church, the church has a special responsibility to dismantle this unjust structure.

The Episcopal Church in 2012, called on all congregations, dioceses, and institutions to reflect upon their history and to encourage them to support Indigenous peoples in their ongoing efforts to exercise their inherent sovereignty and fundamental human rights, to continue to raise awareness about the issues facing Indigenous Peoples, and to develop advocacy campaigns to support the rights, aspirations, and needs of Indigenous Peoples.

Portions of this virtual display are adapted, with permission, from the excellent work of the Mennonite Church USA that was produced by volunteers from the Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery “storytelling group” — Charletta Erb, Sheri Hostetler, and Ken Gingerich. A traveling exhibit was produced by the Beloved Community Initiative for Racial Justice, Healing, and Reconciliation and printed through a generous grant from the Alleluia Fund of the Episcopal Diocese of Iowa and is available to travel to congregations.